SuDS in Scotland; Are we there yet? Comparing the legislative reality with the SuDS philosophy and desired outcomes

Neil McLean, MWH

It is generally recognised that SuDS, in their current form were introduced to the UK through an initiative started by the Forth River Purification Board, one of the Scottish Environment Protection Agency’s (SEPA) predecessor organisations. This was during 1996 – that’s nearly twenty years ago!

It’s fair to say that good progress has been made throughout the UK since then, but I wonder if those of us who were involved in SuDS (or BMPs – Best Management Practices – as they were initially titled) back in the ‘90s would have anticipated the position we are now in.

There are now many thousands of individual SuDS schemes across the UK of varying design, operational effectiveness and aesthetic appeal; some fantastic, others less so. During 2002, in Scotland alone, 767 sites using SuDS, many of which included several different types, were recorded on SEPA’s SuDS database. Activity on the database was stopped in 2002 as it was becoming too much of a burden to keep track of all the new SUDS being constructed, SUDS DataBase; SNIFFER Project SR(02)09.

So where are we now? We have after all had nearly two decades to establish this as “business as usual”.

Scottish legislation, introduced in April 2006, reinforced previous local requirements of planning policy, to enforce the use of SuDS in new developments. Under the “CAR” Regulations [Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations] it is a legal requirement for SuDS to be used to control runoff from developments that drain to the water environment, with few exceptions. SuDS are the law in Scotland! Not only are they the law, but they are routinely installed. That would have been considered as good news, back in the ‘90s. There is a “but” however and it’s been an ongoing “but” for some time. I will explain.

Developers install SuDS for their new sites, as required by law. Some of these look great, while others meet the legal requirement, but look less appealing. Looks are important, whether we are humans looking out of our front window to a nice view, or water voles seeking habitat and refuge to exist. The difference from both perspectives whether the SuDS scheme or component is a pleasant water feature or a “hole in the ground filled with water” is important. Function, of course, is the driver for constructing SuDS and of critical importance.

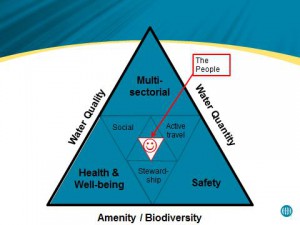

In line with the SuDS triangle, SuDS should provide the following services;

- Water quality; often given a lower priority as flooding continues to hit the headlines;

- Water quantity; flooding benefits and let’s not forget the bottom of the hydrograph, where infiltration can be used to recharge groundwater;

- Amenity; and where appropriate biodiversity.

Additional details can be added to the SuDS triangle to include a more integrated and involving approach, such as the alternative integrated SuDS triangles below and, significantly, with people at its centre.

It is important to remember the SuDS philosophy to “mimic natural drainage”. The extension of this in current thinking, to include the words “where possible” is less helpful and provides a get out clause for those less keen to employ SuDS.

So why is there reticence, on my part, to say that the SuDS initiative has been entirely successful?

The long-term ownership of SuDS needs to be established. “Aye, there’s the rub” as Mr Shakespeare once put it.

Developers install SuDS on new sites, but they generally do not want to be responsible for them. Understandably, they want to build, sell and move on. They don’t want the long-term responsibility of maintaining surface water management measures.

In Scotland, SEPA and the Scottish Government have said that it is desirable to have SuDS adopted and maintained by a body that will exist in perpetuity. Obvious candidates for this are twofold;

- Scottish Water, Scotland’s only water company which is actually an authority rather than a company; and

- Local authorities.

Less obvious ones exist, but the inclusion of specific organisations here may be contentious.

To date, despite there being legislation [Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003] outlining out who adopts SuDS in specific circumstances, Scottish Water have vested, or adopted, very few. It is not that Scottish Water are against SuDS and do not want to adopt SuDS, indeed Scottish Water were the first UK water authority/company to develop design standards for SuDS. Scottish Water’s design standards; “Sewers for Scotland, 2nd Edition” was published in 2007. The details of which were released 2 years prior to this, to allow future designs to meet these standards.

These standards are fairly constrained, with the only options being end of pipe solutions (ponds and basins), many developers choose not to design to these standards and instead compromise to the point that Scottish Water can’t adopt them, due to the way that the law has been written and the standards are laid out – rules is rules! Rightly, they have been strict in their interpretation of their standards, as they are the ones with the responsibility of dealing with these measures long term. Another omplication is that they generally prefer not to share drainage responsibilities without a robust agreement.

Many Scottish local authorities too have had issues relating to SuDS adoption, with their budget being constrained and a general lack of resources to undertake the additional responsibilities associated with adopting SuDS. Although there are some that are more “enlightened” than others and a slow, but positive appreciation of SuDS, especially when SuDS are integrated as multi-functional assets, is gaining speed. Evolution, rather than revolution!

The rather vague arrangement of adoption that exists in Scotland has been criticised by many, but 10 years ago when the legislation was being drafted in Scotland, the foible that is the perceived burden of responsibility, and at the end of the day, COST, was not fully understood. Anticipated, yes; fully appreciated, no. Indeed, cost is almost certainly the cause for the delay in enacting schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act, i.e. the National SuDS Standards in England and Wales.

All this is not to say that SuDS don’t work. Years of experience tells us that they do. They definitely do! But we need to consider the whole picture and the fact that SuDS will need to be maintained.

Two examples below explain;

- A glitch (I hope!); a housing estate and

- The intention; an industrial distribution park.

A large housing estate in Glasgow; SuDS have been employed to control the runoff from a residential redevelopment site. I would call this ‘routine business’! What is disappointing to see is a long, narrow stone-filled base and gabion sided “desert”. It is only a couple of metres deep, but with fence because of the steep sides. So much more could have been made of this to integrate green infrastructure and amenity and a much more appealing asset.

This to me, as a designer, is an opportunity missed. However, there is no doubt that it will reduce flooding considerably and manage pollution to some extent and the bones of the law have been met. What is missing is the bottom side of the SuDS triangle, amenity/biodiversity. The amenity function is prohibited, as the fence around ensures. Biodiversity, will take a long time to establish due to the large amounts of stone used and only with no maintenance unless there are other interventions to remove the barren, stone-desert effect.

Local people have missed out in the opportunity to have been provided with new green infrastructure, creating amenity and a nicer place to live. We must be more involving in the way we consider SuDS designs, with the need for community and stakeholder engagement becoming more urgent.

A distribution park between Glasgow and Edinburgh; this site consists of very large distribution depots, with the majority of traffic on site being heavy goods vehicles. Large areas of hardstanding (roads, loading bay access, car parks, yards and massive roofs) all drain to local site controls (ponds and basins). Large regional controls (ponds) provide additional treatment and flood storage before allowing discharge to the River Almond, formerly Scotland’s most polluted river. The connection between these locations is a simple swale network, which has been allowed to establish itself as a linear wetland.

This linear wetland network uses minimal land and routes flows between the site and regional control measures using a (virtually) pipe-free network. Only two road crossings necessitate the use of pipes, resulting in fantastic habitat and a wide range of biodiversity including frogspawn and dragonflies; all this in what is essentially an industrial estate. Over the last 8 or so years this site has matured into what must be one of the best SuDS locations serving such a high risk (of pollution) site. The SuDS out with the boundary of each premises are maintained by the local authority, who are keen to promote an appealing and successful site to entice new occupiers. Harmony and success at low cost, as landscaping maintenance, whether SuDS or not, would be done by the council anyway.

So although the progression of SuDS in Scotland has become routine, we are not done yet. The same could be said for sewage treatment systems too. Such technologies are 100 years more mature than SuDS technologies, but techniques are still evolving and failures all too often still occur. So let’s not be complacent; let’s continue to take the need and desire for better water quality, flood risk management and integrated infrastructure forward using smart, creative drainage systems that appeal to all.

The better these systems look and function, the more successful they will be, whether you are a human or a water vole!