Maximising the health and wellbeing benefits of blue and green infrastructure in post-COVID cities; incorporating a healthcare agenda

Anna Kenyon, Lecturer in Epidemiology & Public Health, University of Central Lancashire, akenyon10@uclan.ac.uk

It is well known that many types of sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) and blue-green infrastructure (BGI) can deliver multifunctional benefit to local communities, including health and wellbeing benefit.

BGI can form part of SuDS systems, particularly drainage projects through reducing flood risk by attenuating surface water as well as trapping polluting sediments which improves water quality.

However, uptake of BGI has been limited and interdisciplinary projects that combine health and drainage objectives are rare.

This is partly due to a lack of evidence and guidelines for practitioners designing SuDS that can deliver drainage and health benefits. Our recent publication using evidence from the Netherlands and the UK, for example, found that while multifunctionality and interdisciplinary working was on their agenda, local authority practitioners often felt they lacked a framework for achieving such benefits (Willems, Kenyon, Sharp and Molenveld, 2020).

Our report Designing Blue Green Infrastructure (BGI) For Water Management, Human Health, And Wellbeing covering BGI design and health pulls together the evidence of the potential for BGI to deliver health benefit and offers strategies for design to do just that.

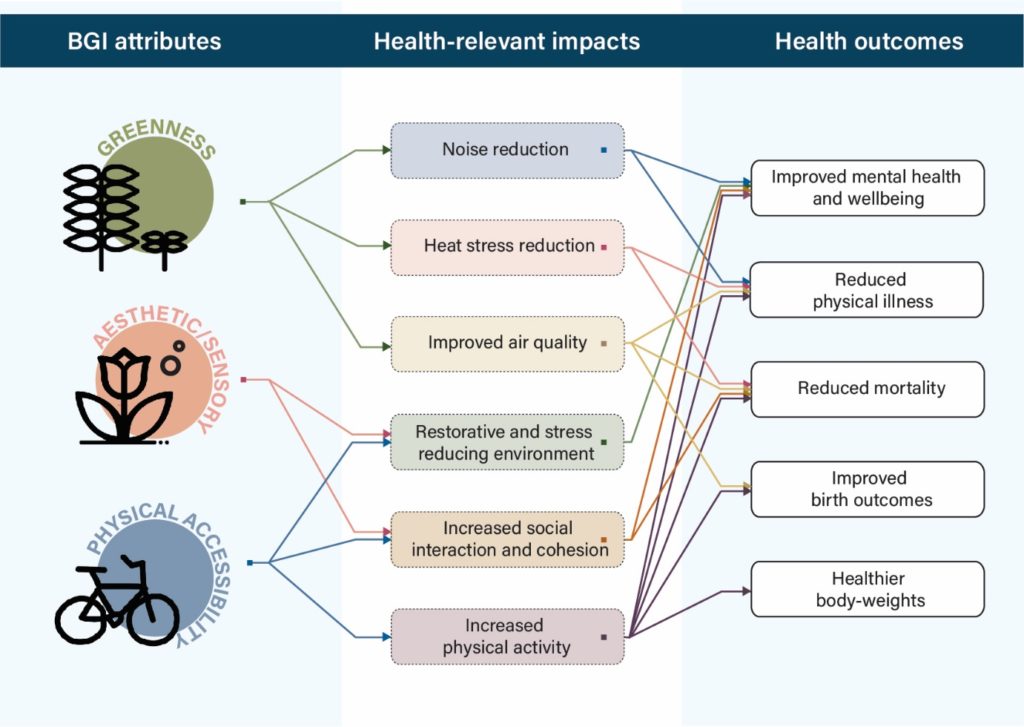

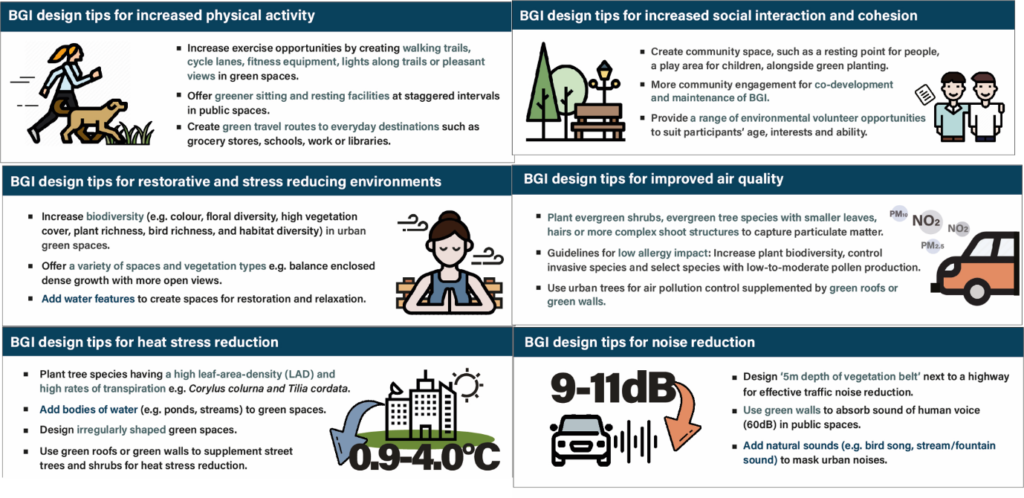

We identified six health outcomes that can be supported by BGI (Figure 1) including improved physical and mental health and healthier body weights. To help achieve this, the report offers design tips for SuDS which can reduce noise pollution, heat stress and human stress; improve air quality and provide an environment that supports social cohesion and physical activity (Figure 2). These designs range from large scale approaches (such as part of creating walking and cycling routes to facilitate physical activity), medium scale approaches (such as the design of pocket parks and rain gardens) to small scale tweaks that can be made to existing BGI plans to specifically leverage health benefit, for example, selecting plants with leaf shapes that maximise heat stress reduction or selecting species that augment air pollution control (Fig. 2). Such BGI interventions can be applied to some types of SuDS, for example, a constructed wetland, for example, may have particular types of plants for water quality benefits. In this way, diverse SuDS projects that incorporate BGI can be designed to integrate a mutual agenda for drainage and health.

Figure 1:

Figure 1: Schematic pathways showing different forms of BGI exposure, with potential for health-relevant impacts and health outcomes (Kenyon, A and Choe, E. 2020. In Choe, Kenyon and Sharp, 2020)

Delivering multifunctional blue and green infrastructure is becoming increasingly recognised as an important factor for post-Covid urban development. Covid has accelerated the ‘decline of the high street’ as demonstrated by, for example, the recent collapse of high street retail owner Arcadia Group.

Concurrently, lockdown has triggered people’s renewed interest in nature and outdoors (Natural England, 2020), and has set the stage for redefining and redesigning urban spaces through ecological restoration, for example, through ‘rewilding’ which is been increasingly on the urban design agenda in recent years (Hall, 2019, Jepson and Schepers, 2016).

BGI has also been identified as having potential to ameliorate rising health inequalities (Public Health England, 2020), another pressing concern in the wake of Covid-19 (BMJ, 2020).

Sustainable drainage systems that incorporate BGI have potential to deliver not just better surface water management but a host of multifunctional benefits. Good design can harness this potential and capture the blue green zeitgeist of the post-Covid urban spaces. This can ensure that our urban areas can continue to thrive and offer evolving and multifunctional spaces for the people that use them.

Figure 2: BGI design tips for health (Choe, Kenyon and Sharp, 2020)

Bibliography

Choe, E., Kenyon, A. and Sharp, L., 2020. Designing Blue Green Infrastructure (BGI) For Water Management, Human Health, And Wellbeing: Summary Of Evidence And Principles For Design. [online] University of Sheffield. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.13049510> [Accessed 12 December 2020].

BMJ 2020. Covid-19: Tackling health inequalities is more urgent than ever, says new alliance, 371: m4134

Hall, C., 2019. Tourism and rewilding: an introduction – definition, issues and review. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), pp.297-308.

Jepson, P. R., and F. Schepers, 2016. Making Space for Rewilding: Creating an Enabling Policy Environment. Rewilding Europe.

Natural England, 2020. A Rapid Scoping Review Of Health And Wellbeing Evidence For The Framework Of Green Infrastructure Standards.

Public Health England, 2020. Improving Access To Greenspace A New Review For 2020.

Sweeney, O., Turnbull, J., Jones, M., Letnic, M., Newsome, T. and Sharp, A., 2019. An Australian perspective on rewilding. Conservation Biology, 33(4), pp.812-820.

Willems, J., Kenyon, A., Sharp, L. and Molenveld, A., 2020. How actors are (dis)integrating policy agendas for multi-functional blue and green infrastructure projects on the ground. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, pp.1-13.